Graceland Cemetery is the premiere resting place – and showplace – for a “who’s who” of Chicago’s most outstanding architects. From the original designers of Graceland, landscape architects H.W.S. Cleveland and Ossian Simonds, partners Holabird and Roche, who designed the Cemetery’s buildings, to William Le Baron Jenney, the father of the skyscraper, the great Louis Sullivan and right up to modern masters like Mies van der Rohe and Khan, their influence on commercial and residential spaces spans centuries past, through the present and likely long into the future. Graceland Cemetery is proud to pay homage to Chicago’s great architects with examples of their work and summaries of their lives.

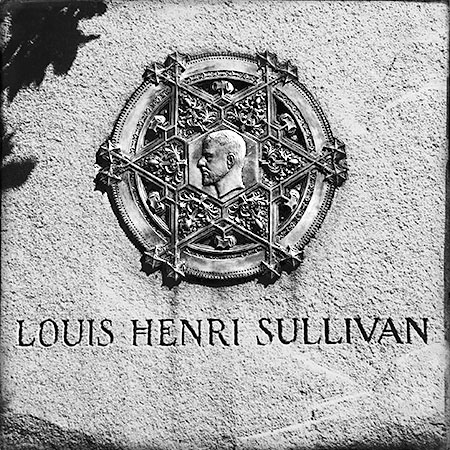

Louis Sullivan, 1856 -1924

Louis Sullivan, 1856 -1924

For the man whose designs and writings helped create modern architecture, you have to look somewhere other than Sullivan’s Graceland resting place for monuments to his own life. While Sullivan designed two tombs for others in Graceland, his own simple, rough-hewn headstone at his parent’s gravesite belies his great contributions as the “Father of the Chicago School of Architecture.” An outstanding example of his work still stands in Chicago – the Carson Pirie Scott store, one of the few Sullivan buildings that remain in the Loop.

John Root, 1850 –1891

John Root, 1850 –1891

Root, one of the founders of the leading Chicago Architecture firm of Burnham and Root, is one of the fathers of the Chicago “school” of architecture. Although Root spent his career breaking away from architectural tradition, members of his firm created a totally traditional Celtic cross, which Root had admired in English cemeteries. Charles Atwood chose a Druid style, and Jules Wegman provided the design, which includes one of Root’s drawings, the entrance to the Phoenix Building, which did not rise from its own ashes when it was demolished in 1959.

Daniel Burnham, 1846 - 1912

Daniel Burnham, 1846 - 1912

Burnham, a partner of John Root, became known for his dictum, “Make no little plans.” And indeed, he practiced what he preached. He was chief of construction for the 1893 Columbian Exposition, and his Chicago Plan of 1909 is the reason that Chicago’s lakefront has been preserved for the enjoyment and recreational use of its citizens and tourists.So it seems fitting that his final resting place is on a pleasant, wooded isle in the lake at Graceland.

Howard Van Doren Shaw, 1868 - 1926

Howard Van Doren Shaw, 1868 - 1926

The designer of the Goodman lakeside mausoleum, Shaw was a contemporary of Frank Lloyd Wright and others of the Prairie School of Architecture, but not one of the group. His designs remained traditional, which made him a favorite of wealthy residents of Lake Forest and other North Shore communities, for whom he designed many country homes.

The bronze ball on top of the elegant granite pillar contains the words of the 23rd Psalm.

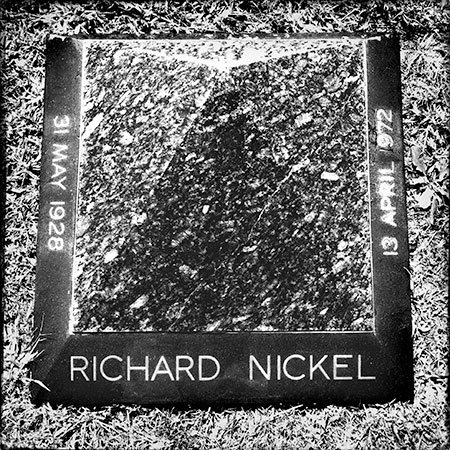

Richard Nickel, 1928 – 1972

Richard Nickel, 1928 – 1972

Nickel was an architectural photographer who met his untimely death by trying to salvage as much of Adler & Sullivan’s Stock Exchange on LaSalle Street before it was completely demolished. His body was found in the rubble weeks after his disappearance. The artifacts he collected and his photographs are about all that’s left of many of the Adler & Sullivan buildings that once graced the Loop.

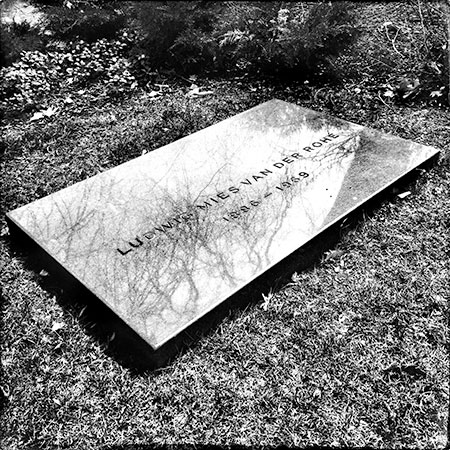

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, 1886 -1969

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, 1886 -1969

Said – and meant – “less is more.” Leader of the International Style. Spent his life perfecting the “universal” building – bones of steel, skin of glass. See the Federal Center in the Loop. His most appropriate black granite marker was designed by his grandson, architect Dirk Lohan.

Fazlur Khan, 1929 – 1982

Khan, the first structural engineer to be named a partner at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, has his most impressive monument in downtown Chicago: the 110-story Sears Tower. It’s there that his “tube” theories – framed, trussed and bundled – literally reached their highest point, and where his most famous quote is engraved on a plaque – “The technical man must not be lost in his own technology. He must be able to appreciate life; and life is art, drama, music, and most importantly, people.” In 1998, Chicago named the intersection of Jackson and Franklin at the foot of the Sears Tower “Fazlur R. Khan Way.” His other masterworks include Chicago’s 43-story Dewitt-Chestnut Apartments and 100-story John Hancock Center.

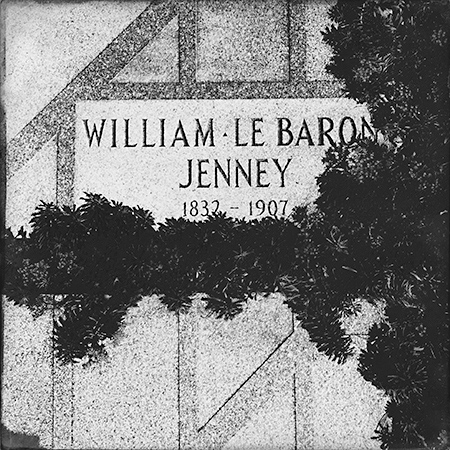

William Le Baron Jenney, 1832 - 1907

William Le Baron Jenney, 1832 - 1907

Known as the “Father of the Skyscraper,” Jenney studied engineering and architecture at Harvard and in Paris, where he graduated one year after Gustave Eiffel. Jenney served as Grant’s and Sherman’s engineer during the Civil War, rising to the rank of Major, then moved to Chicago in 1867. He designed the first fully metal-framed skyscraper, the Home Insurance Building, built in 1885, four years before Eiffel’s more famous tower. Although Jenney’s creation was demolished in 1931, his heritage lives on through the apprentices he mentored, and who became leading architects in their own right, including Louis Sullivan, Daniel Burnham, William Holabird and Martin Roche. When Jenney died, in 1907, his ashes were scattered over his wife’s grave at Graceland. (Note: It’s no longer allowed). One hundred years later, his memory was properly honored with a new gravestone, dedicated in June of 2007.

Marion Mahony Griffin, 1871 - 1971

Marion Mahony Griffin became the first licensed female architect in the U.S. and the only woman in the Oak Park Studio of Frank Lloyd Wright. Some claim she was the real talent behind the Prairie School for which Wright is given credit. Her drawings helped her husband, Walter Burley Griffin win an international competition to design Australia’s new capital, Canberra. In Australia, India and America, she and her husband implemented their belief that “beyond blending beauty and function, buildings should be ecologically sound… They should provide an environment enhancing the physical, psychological and spiritual well-being of the people who work in them.”

Her remains have been moved from an unmarked grave to a columbarium with a plaque featuring her name and one of her flower drawings. Recently, the Art Institute of Chicago established a website dedicated to her revealing work, “The Magic of America,” at www.artic.edu/magicofamerica.

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, 1895 - 1946

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, 1895 - 1946

Moholy-Nagy attended the Bauhaus, a new kind of school of architecture, art, and design, from 1923-1928. He was able to incorporate the methods and exercises he learned while attending the Bauhaus into his own school, The School of Design in Chicago, which opened February 1939. He aimed at educating the whole person and he placed emphasis on teamwork and experimentation. In 1944, the school was reorganized and renamed The Institute of Design in Chicago. In 1949, the school became a department of the Illinois Institute of Technology, where it continues today, a direct descendant of Moholy-Nagy's school. Moholy-Nagy was an accomplished artist in many fields including painting, sculpting, photography and film. In 2003, The Moholy-Nagy Foundation was formed in response to the continuing interest in his life and works. Their website is www.moholy-nagy.org.

Dwight Heald Perkins, 1867 -1941

In 1879, at the age of 12, Perkins moved to Chicago from Tennessee with his family. After two years of studies and one year of teaching at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Perkins returned to Chicago in 1888. Perkins established his own architectural practice on January 1, 1894 with a commission from the Steinway Piano Company to design a new building. He invited some friends to share the office space with him and thus Steinway Hall and the Prairie School of Architecture had their beginnings. His respect for natural materials and eliminating excess details in his designs, were hallmarks of the Prairie School. In 1905 Perkins was appointed as the chief architect for the Chicago Board of Education and held this position until 1910. Acknowledged as a pioneering architect, throughout the 1910s and the early 1920s he specialized in schools, utilizing the social agenda and the aesthetics of the Arts and Crafts movement. Known to combine a variety of styles into his work, Perkins incorporated the functional style of the architecture known as the Chicago School into many of his designs. His designs included Albert Lane Technical High School (1908, ¬1910), Carl Schurz High School (1908, ¬1910), and the Lion House (1912) at Chicago’s Lincoln Park Zoo. Perkins active participation in preserving open space helped to establish the Cook County Forest Preserve. He is buried in the family lot in Graceland Cemetery along with many other family members including his son Lawrence Bradford Perkins, also a noted Chicago architect, who founded the architectural firm of Perkins & Will in 1935.

Bruce Goff, 1904 -1982

Bruce Goff was born in 1904 in Alton, Kansas. Goff’s family settled in Oklahoma where he demonstrated a true talent for drawing and became apprentice with the architectural firm of Rush, Endacott and Rush in Tulsa at the age of twelve. Self-educated Goff employed creative free association and borrowed materials in his designs. In his private practice, while remaining sensitive to the needs of the client and the constraints of the site, Goff integrated exposed structure and spatial complexity with a degree of enhancing details. This technique was known as organic architecture; a development of concepts started by his mentor, Frank Lloyd Wright. It was this attention to detail that set him apart as an architect and why he is regarded as one of the masters of organic architecture.

Goff came to Chicago, Illinois in 1934 and worked briefly for Alfonso Iannelli. While supporting himself as a freelance residential designer, he was offered a part-time teaching position at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts where he explored theories on “free architecture,” which stresses that architecture is not exempt from the need to break new artistic ground and that buildings should be seen as objects of beauty. While living in Chicago he also worked for the manufacturer of Vitrolite, a patented form of architectural sheet glass introduced in the 1930’s.

In 1942 Goff became a professor at the School of Architecture at the University of Oklahoma, rising to the position of chairman of the school, which he held until 1955. Two of his most famed residence projects, the Ruth Ford house in Aurora, Illinois, and the Eugene Bavinger house in Oklahoma were both built during his time at the University gaining his private practice significant attention. Goff’s last project, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s Pavilion for Japanese Art was built to house Joe Price’s Shin’en Kan collection of Japanese paintings.

He died in Tyler, Texas on August 4, 1982; on October 7, 2000 his cremated remains were buried at Graceland Cemetery with a marker designed by Grant Gustafson that incorporates a glass cullet fragment salvaged from the ruins of the Joe D. Price House and Studio. Through the Shin’en Kan Foundation, Inc. and Goff executor, Joe Price, the Art Institute of Chicago was given Goff’s wide-ranging archive in 1990. A major retrospective exhibition of his work was featured in 1995 at the Art Institute of Chicago with an accompanying catalog, The Architecture of Bruce Goff, 1904-1982: Design for the Continuous Present.